Why Warsaw still casts Berlin as adversary while Germany moves closer on security

Anti-German grievance is a default in Poland’s polarised, nuance-free politics.

In an era when pronouns are often the trigger for political fury, Poland’s latest storm has centred on a pronoun too. However, in this very Polish affair, the issue isn’t about gender, but rather World War Two and, of course, Germany.

A row sparked by Nasi chłopcy (“Our boys”), the title of a new exhibition in the northern city of Gdańsk about Poles conscripted into Hitler’s army, shows how easily history is weaponised in Poland’s polarised politics.

The “Our boys” row fits a larger pattern. The very word “our” jarred in a country where Germany remains the historic enemy.

Anti-German rhetoric is growing louder across Polish politics. This sentiment shaped the recent presidential campaign, has fused with migration fears along the western border and now features in sermons as bishops echo nationalist language.

Germany is framed as an eternal enemy bent on destroying Polish sovereignty, now wrapped in smiles and EU banners, sending migrants where once it sent panzers.

Yet this anti-German mood comes at an ironic moment. After years of Polish complaints that Berlin was naïve about Russia, Germany has overhauled its foreign and defense policy, boosting NATO spending targets and deploying troops to NATO’s eastern flank.

German leaders now speak in Warsaw’s language, warning that if Ukraine falls, Putin’s troops could reach the Polish border.

Rather than drawing Poland and Germany together, these moves are drowned out by grievance politics that thrive in Poland’s polarised, nuance-free political landscape.

The trigger

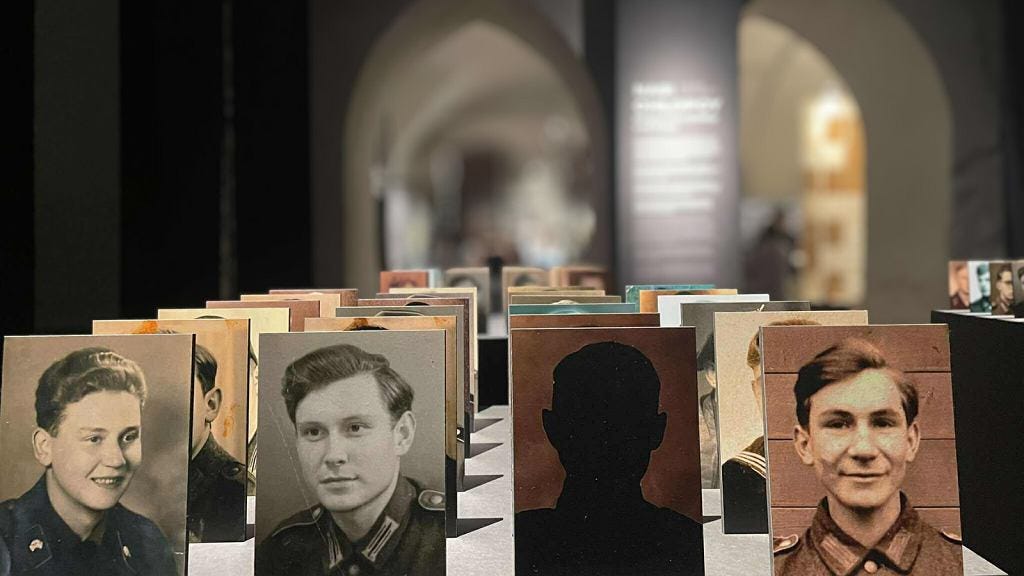

The storm began with “Our boys”, the title of a new exhibition at the Gdańsk Museum, curated with the Museum of the Second World War and the Polish Academy of Sciences.

It tells the complex story of how tens of thousands of Poles from annexed regions like Pomerania and Silesia were forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht after 1939.

This is not marginal history. Some estimates suggest more Polish citizens served in Hitler’s army than in the Polish wartime underground. For many families, this history remained buried for decades after the war in silence and shame.

But the exhibition’s nuance evaporated as soon as it entered Poland’s polarised political battlescape. The suggestion that these boys were “ours” was a pill too bitter to swallow for many in Poland’s political class.

President Andrzej Duda, the right-wing incumbent, called it a “moral provocation” and warned that “presenting soldiers of the Third Reich as ‘our’ boys falsifies history.”

Mariusz Błaszczak, a former defence minister from the nationalist-conservative Law and Justice party (PiS), now in opposition, accused the exhibition of promoting a “German historical agenda.”

Defense Minister Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, leader of the agrarian-centrist Polish People’s Party, declared: “Our boys are the Poles who defended their homeland to the last drop of blood.”

Law and Justice leader Jarosław Kaczyński went the farthest, questioning whether the exhibition aimed to dilute German responsibility for World War Two, or “even attribute it to the Poles.”

Not wanting to be left out, Adam Szłapka, government spokesman from the centrist Civic Coalition (KO), said the exhibition’s very title was “unacceptable.”

What the exhibition tried to present as a nuanced and tragic episode was flattened into a crude binary driven by the demands of the bitter contemporary tribal rivalries in Poland.

Grievance politics

Poland’s recent presidential election offered a familiar window onto how anti-German grievance runs through the DNA of its electoral politics.

Karol Nawrocki, the PiS-backed candidate, a nationalist historian and former head of the Institute of National Remembrance, Poland’s official body for investigating historical crimes, built his campaign around “unfinished history.”

He promised to reopen Warsaw’s 2022 demand for 6 trillion złoty (€1.4 trillion) in WWII reparations from Germany, telling crowds he would “fight for justice for six million murdered Poles from day one.”

Nawrocki linked Germany’s wartime crimes with Berlin’s influence inside today’s European Union, casting Brussels’ rule-of-law pressure on Poland as a German project.

His campaign videos showed him laying wreaths at Wehrmacht massacre sites, while PiS-friendly media cut between footage of his rallies and images of Westerplatte, the site of Germany’s 1939 invasion.

The unmistakable message was that Germany once destroyed Poland, Germany now blocks Polish ambitions, and only a strong Polish president can resist.

His opponent, Rafał Trzaskowski of the Civic Coalition (KO), a liberal-centrist and mayor of Warsaw, called for “normal, interest-based partnership” with Germany and the EU.

PiS and its media echo-chamber branded him the “Berlin candidate.”

Bordering on history

Just as the election ended, another opportunity arose to rattle the anti-German sabre. In July, the government reinstated border checks with Germany for 30 days, citing a spike in irregular crossings and an “imbalance” after Berlin tightened its own frontier earlier in the year.

Tusk framed the step as reciprocity, not a retreat from European integration, but the gesture quickly took on a symbolic life.

PiS MPs accused him of “serving German interests.” Krzysztof Bosak, a far-right MP from the Confederation party, accused Germany of delivering “van-loads of migrants” to Poland.

He claimed Polish border guards were “treated like taxi drivers” and alleged that many of the migrants returned had never set foot in Poland, while criticising the government for failing to check identities or origins.

Far-right activists led by Robert Bąkiewicz, head of the so-called Border Defense Movement, a vigilante anti-migrant group, patrolled the frontier and livestreamed their “citizens’ checks,” calling Germany the aggressor in a new “hybrid war.”

Normalising extremism

The border row didn’t just empower mainstream parties but it also gave space for fringe figures and hardliners to push their rhetoric further, making anti-German grievance sound increasingly normal.

Grzegorz Braun, a far-right MP who recently splintered from the Confederation alliance, and Bąkiewicz, the radical nationalist organiser, have long traded in grievance politics.

But their language is no longer fringe. Braun frames Germany as a renewed aggressor, warning that “Germany last crossed our border in 1939 and is doing it again now, with migrants.”

Bąkiewicz calls Germany’s migration policy “a hybrid war” and casts his vigilante patrols as patriotic resistance to a “Fourth Reich.”

Braun’s six percent in the first round of the presidential election and President Duda’s recent pardon for Bąkiewicz show how these extreme voices are gaining acceptance.

Even senior Catholic clergy have joined in. Bishop Antoni Długosz praised Bąkiewicz’s vigilantes as a justified response to German “Islamisation” of Europe, while Bishop Wiesław Mering declared from the pulpit that “Germany will never be Poland’s brother.”

As the country’s political centre of gravity has clearly shifted right, these voices are becoming mainstream.

Germany’s ‘Zeitenwende’

While Poland’s political mood turns increasingly hostile toward Germany, Berlin itself has been moving steadily toward Poland’s strategic worldview.

In February 2022, Chancellor Olaf Scholz delivered his Zeitenwende “turning point” speech, declaring Russia the primary threat to European security and promising a shift from Germany’s long tradition of Ostpolitik, West Germany’s Cold War-era policy of engagement with the Soviet bloc.

Since then, Berlin has followed through. In 2024, Germany finally met NATO’s two percent of GDP defense spending threshold, after decades below it, and plans to raise this further in coming years.

On April 1, Germany activated a 5,000-strong armoured brigade in Lithuania, its first permanent foreign deployment since 1945, answering Poland’s call for “deterrence by defense” on NATO’s eastern flank.

Germany has also become the world’s second-largest supplier of heavy weapons to Ukraine and ended its decades-long dependence on Russian gas, with the Nord Stream 2 pipeline officially abandoned.

Berlin’s political class now talks much like Warsaw. Former Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock warned that if Ukraine fell, Putin’s troops could “reach the Polish border,” a line long used in Warsaw.

Why grievance endures

The persistence of anti-German rhetoric in Poland’s politics is no accident. It reflects the deeper mechanics of a polarised duopoly where politics is driven less by policy and more by identity, loyalty and grievance.

Eighty years after World War Two, historical trauma is still political currency. The memory of German crimes is emotional capital, easily mobilised to sharpen divisions and prove patriotic credentials.

Karol Nawrocki’s pledge to “fight for justice for six million murdered Poles from day one” is grievance politics in its purest form.

For polarisation to work it needs simplification. In Poland’s binary political culture, politics thrives on friend-or-foe choices, and Germany is the perfect adversary, familiar from textbooks, family stories and wartime memorials.

This has become a Pavlovian reflex. From PiS to bishops to far-right activists, criticising Germany has become so automatic that the uproar over the “Our boys” exhibition felt less like a debate and more like an inevitability.

European implications

The paradox has consequences well beyond Poland. Warsaw relies on Germany’s military build-up and energy shift to strengthen NATO’s eastern flank and help Ukraine.

Poland’s loud, grievance-driven politics risks complicating this new alignment. Anti-German narratives make practical cooperation harder, whether on defense, military deployments or energy projects.

For Ukraine, that means added friction at a moment when unity matters most. For Russia, it offers easy material to exploit divisions inside NATO’s eastern front.

At the very moment Germany and Poland are finally pulling in the same direction on security, Poland’s two-party duopoly is dragging the relationship backwards.

Poland’s politics reveals a simple truth: the need for an enemy runs deeper than the need for security.

The “Our boys” row fits a larger pattern. The very word “our” jarred in a country where Germany remains the historic enemy, implying belonging where most politicians insist there can be none.

Yet this anti-German mood comes at an ironic moment. After years of Polish complaints that Berlin was naïve about Russia, Germany has overhauled its foreign and defense policy, broken with Ostpolitik, boosting NATO spending targets and deploying troops to NATO’s eastern flank.

A version of this article first appear at TVP World.

Poland and Central and Eastern Europe are now at the heart of European politics. As the continent’s centre of gravity shifts eastward, understanding this region is key to understanding Europe itself.

Poland Watch is your guide. With in-depth analysis, sharp insight, and clear explanations, I help readers make sense of the strategies, tensions, and turning points shaping Poland and its neighbours today.

Subscribe for regular coverage of the region’s political shifts, power plays, and emerging trends.

Thank you. An objective and comprehensive summary of what has been happening.